SOLO

Ciaccia Levi, Milano(IT)

Curated by: —

Disegno

23.11.24—18.01.25

Candide

In occasione della Milano Drawing Week, curata dalla Collezione Ramo, Ciaccia Levi è lieta di presentare

Candide, la seconda mostra personale di Leonardo Devito con la galleria.

Invitato a scegliere un’opera dalla Collezione Ramo, Devito ha selezionato Boat IV, 1957, di Domenico

Gnoli, con cui instaurare un dialogo. L’esposizione presenta una serie di nuovi lavori su carta, legati a un

testo che è particolarmente caro all’artista: Candido di Voltaire. Nel romanzo, una serie di eventi catastrofici

si sussegue a causa delle decisioni semplici e ingenue del protagonista, che, in poche pagine, compie un

viaggio che lo porta a girare mezzo mondo. Il tutto è raccontato con un ritmo e una leggerezza che creano un

contrasto piacevole tra la drammaticità degli eventi, il cinismo filosofico che pervade il romanzo e la

narrazione spassosa e divertente.

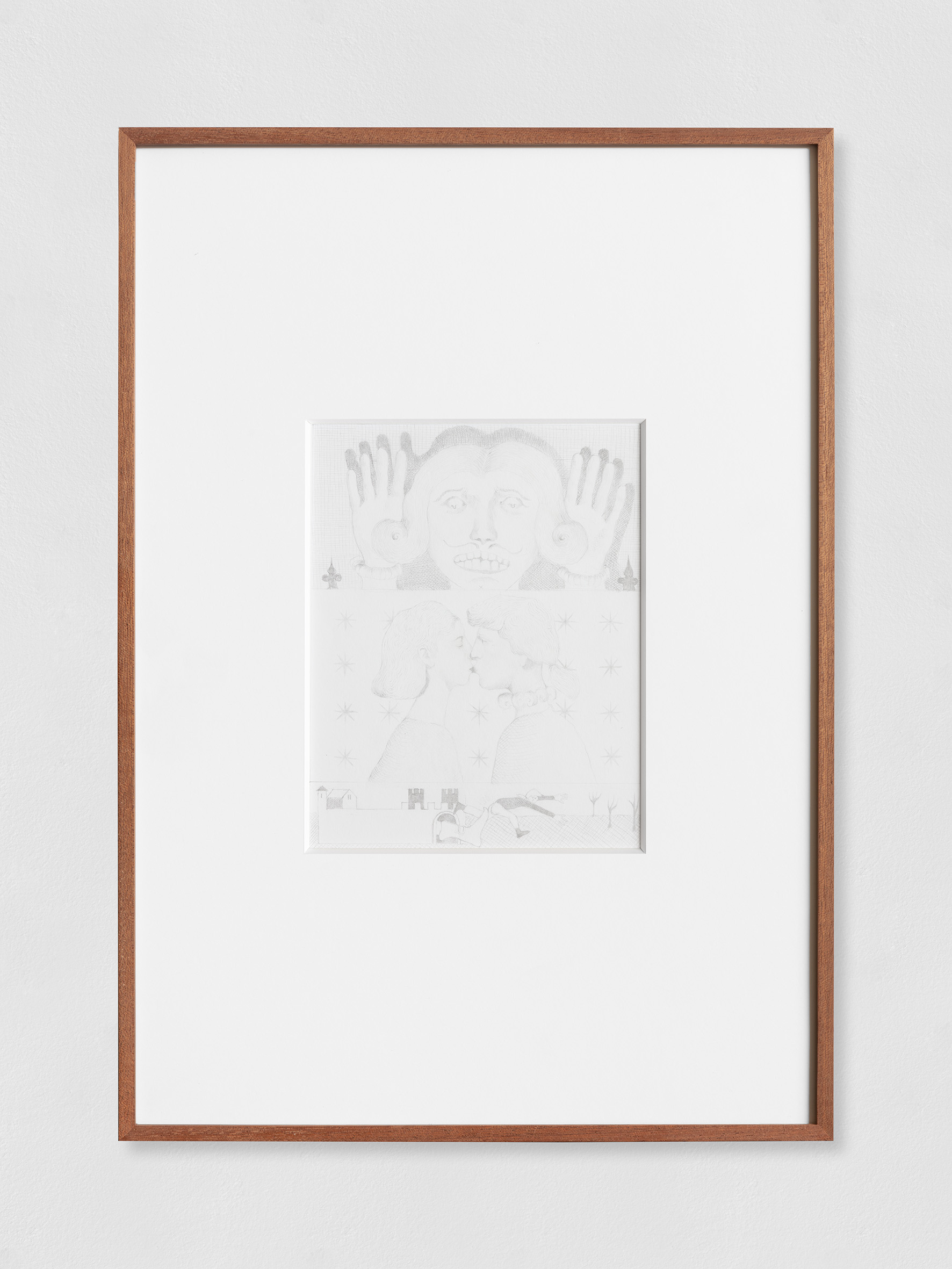

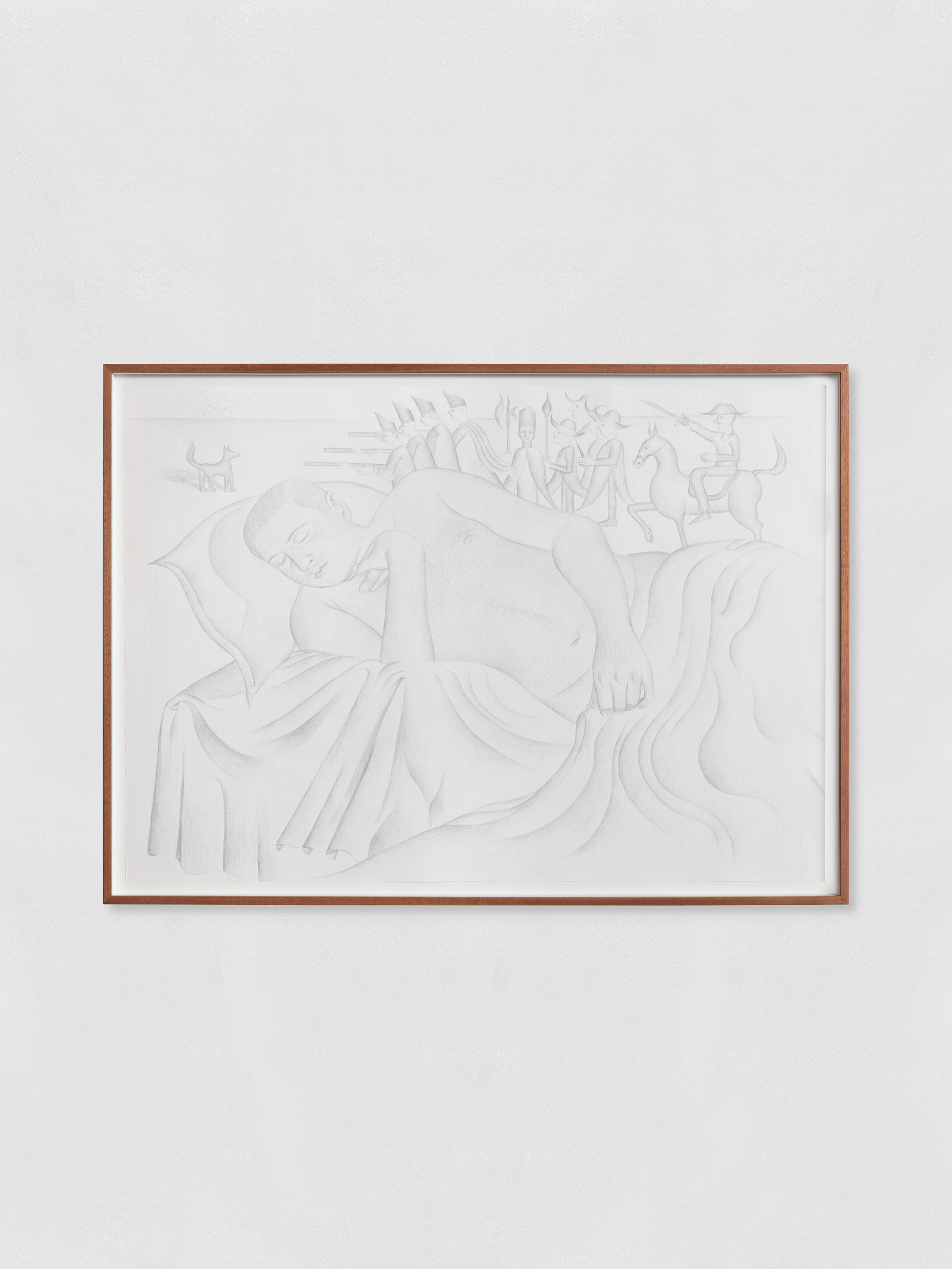

In mostra saranno presenti tre gruppi di lavori. Il primo consiste in cinque illustrazioni di Candido, realizzate

con matita a mina molto dura, in imitazione della tecnica dell’acquaforte. Il secondo è una serie di punte

d’argento, in cui Devito disegna immagini ispirate al romanzo. Infine, il terzo gruppo comprende due disegni

di grande formato, che richiamano la tecnica pittorica dell’artista.

Questi lavori si collegano al personaggio di Candido e all’ingenuità stessa del protagonista, suggerendo l’idea

di una storia che, attraverso la tecnica del disegno, riesce a distaccarsi dalla realtà e a semplificarla, pur

mantenendo intatta la sua essenza.

SOLO

Ciaccia Levi, Parigi (FR)

Curated by: —

Pittura, Scultura

13.09.24—13.10.24

Teatrino

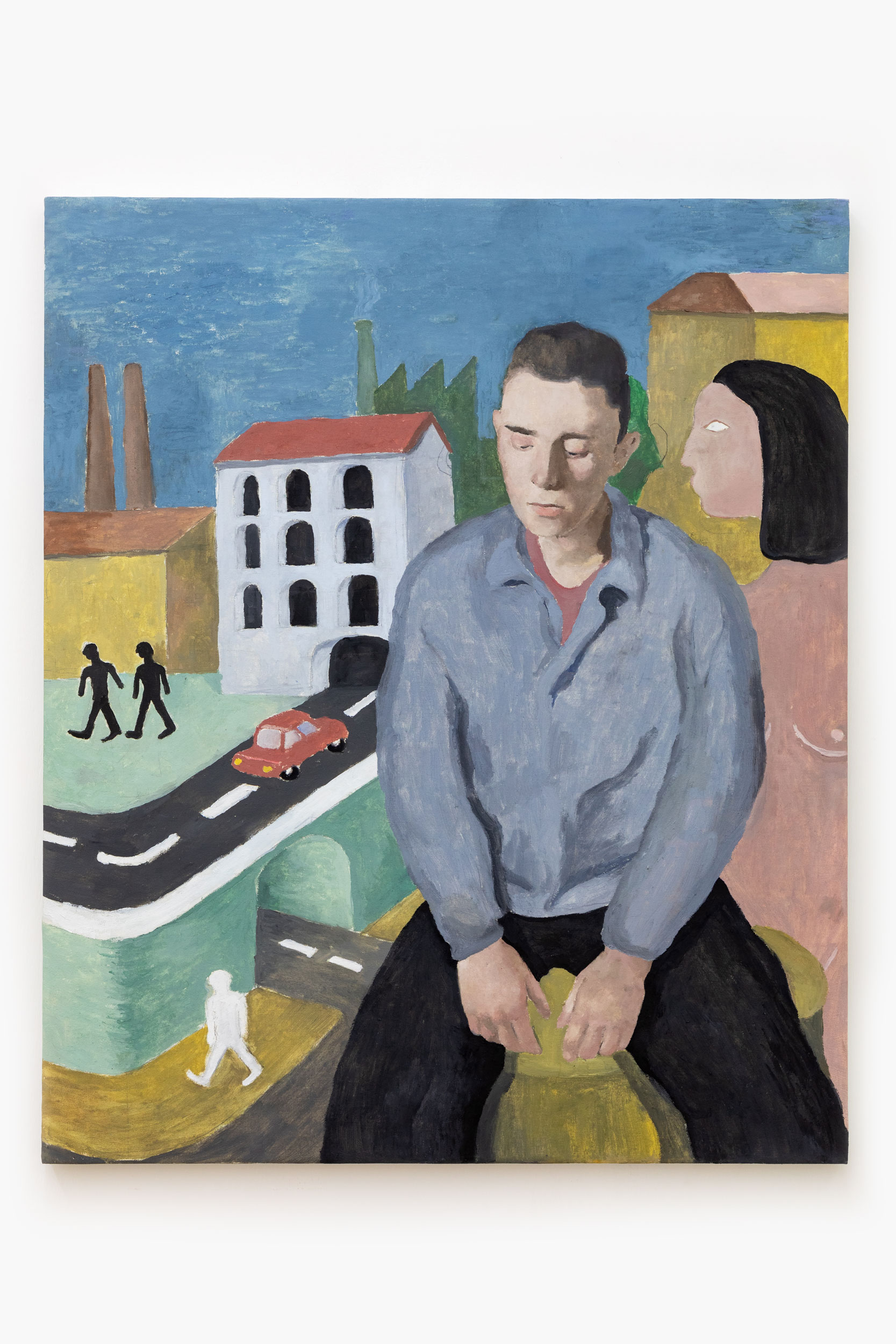

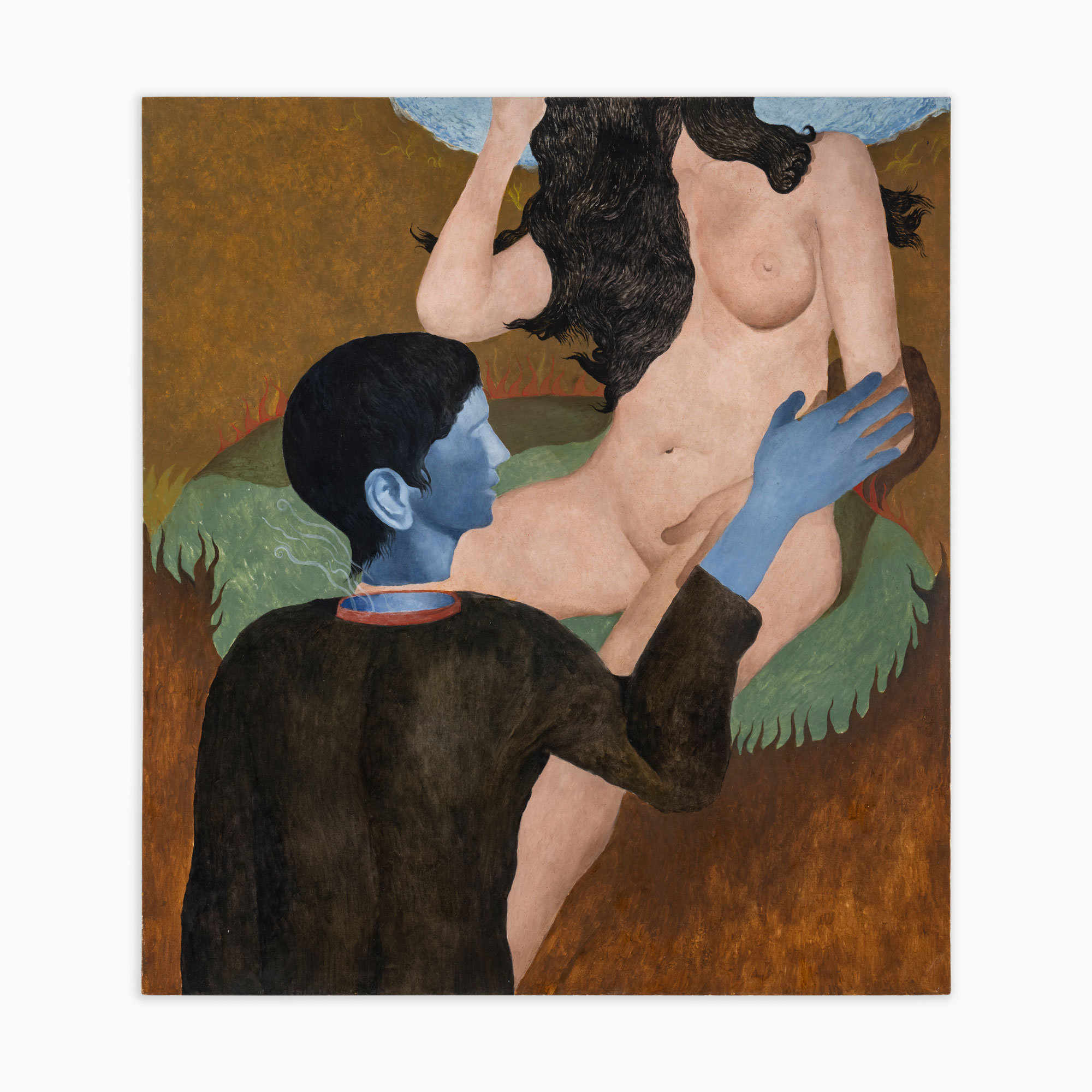

Teatrino is an exhibition project by the Italian artist Leonardo Devito (Florence, 1997) created for his first

solo show at the Galleria Ciaccia Levi in Paris.

Paintings and high-reliefs weave a narrative dedicated to the imagery of spectacle, populated by actors and characters, both real and imaginary, who stage performances balanced between a tragic sense of life, alienation, and comedy. Some of these subjects, such as Kafka's trapeze artist and hunger artist—protagonists of the writer's last stories, one realizing himself in isolation on the trapeze and the other in abstaining from food—turn their lives into a work of art, driven by a devotion to art that often remains misunderstood by the public. Other characters seem to belong to a fairy-tale world, catapulted into an ahistorical time. As we enter the exhibition, a sense of familiarity pervades our vision, as if we are recalling a gesture, a gaze, a story from the depths of memory.

In this narrative of a lost world, we encounter various iconographic references, especially in the paintings,

which relate to the artist's personal imagination and a repertoire of images that form a personal "ideal

museum" yet are also familiar to the public, connected to art history, literature, and graffiti. Devito's works reveal a strong connection with the research of certain 20th-century artists, such as Mario Sironi and Felice Casorati, or with art movements like Metaphysical Art. However, the other reality to which this combination of unusual elements refers is identifiable and contemporary, albeit ambiguous, estranging, and illogical. In the artist's works, the inclusion of a personal detail or a naive element, the use of irony, or an incorrect proportion lightens the severity of the composition, triggering repeated linguistic and temporal shifts. The

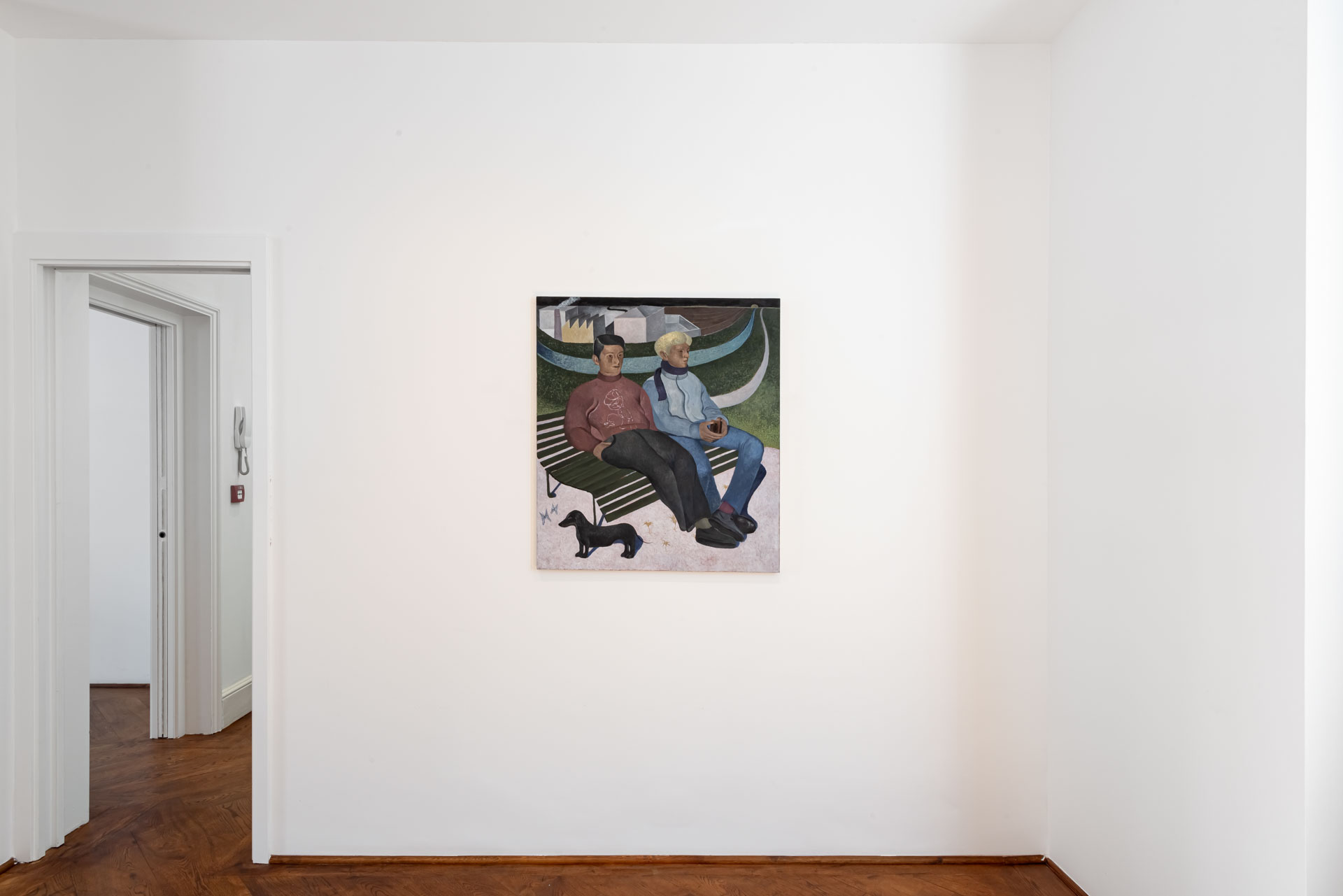

bright colors of the hair, the relaxed poses of the young subjects, and their attire convey a sense of closeness to our time, contrasting with the drapery and folds of fabrics, the monumental yet often inharmonious hands and bodies, the defined partings, the features clearly referencing the physiognomy of sculpture, and the dark, material colors.

The more or less explicit reference to other artistic productions or homage to another artist is

a practice that has intrigued many throughout the centuries, including the historical avant-gardes of the 20th century. In a different manner, artists have re-presented and represented the past. Devito anchors the past to the present with a language rich in references and through a plastic structure that seems to halt the time of action, captured in its immanence and confined in a visual and mental space where the outside does not refer to anything else—even when a de Chirico-like window shows a portion of the sea (Arrival of the Chimney Sweep Dogs).

Our vision intercepts those elements foreign to the formal and narrative order that appear almost epiphany-like between the folds of a fabric or on a floor, such as the acrobats on horses (Equilibrist) or the elf-like ears of the Puppeteer. These elements establish an elusive relationship with the context but do not point to another reality; they plunge us into the space of imagination, where thought has not yet transformed into words, where references are untied and forms are liberated, allowing us to restart the game of associations and recognitions.

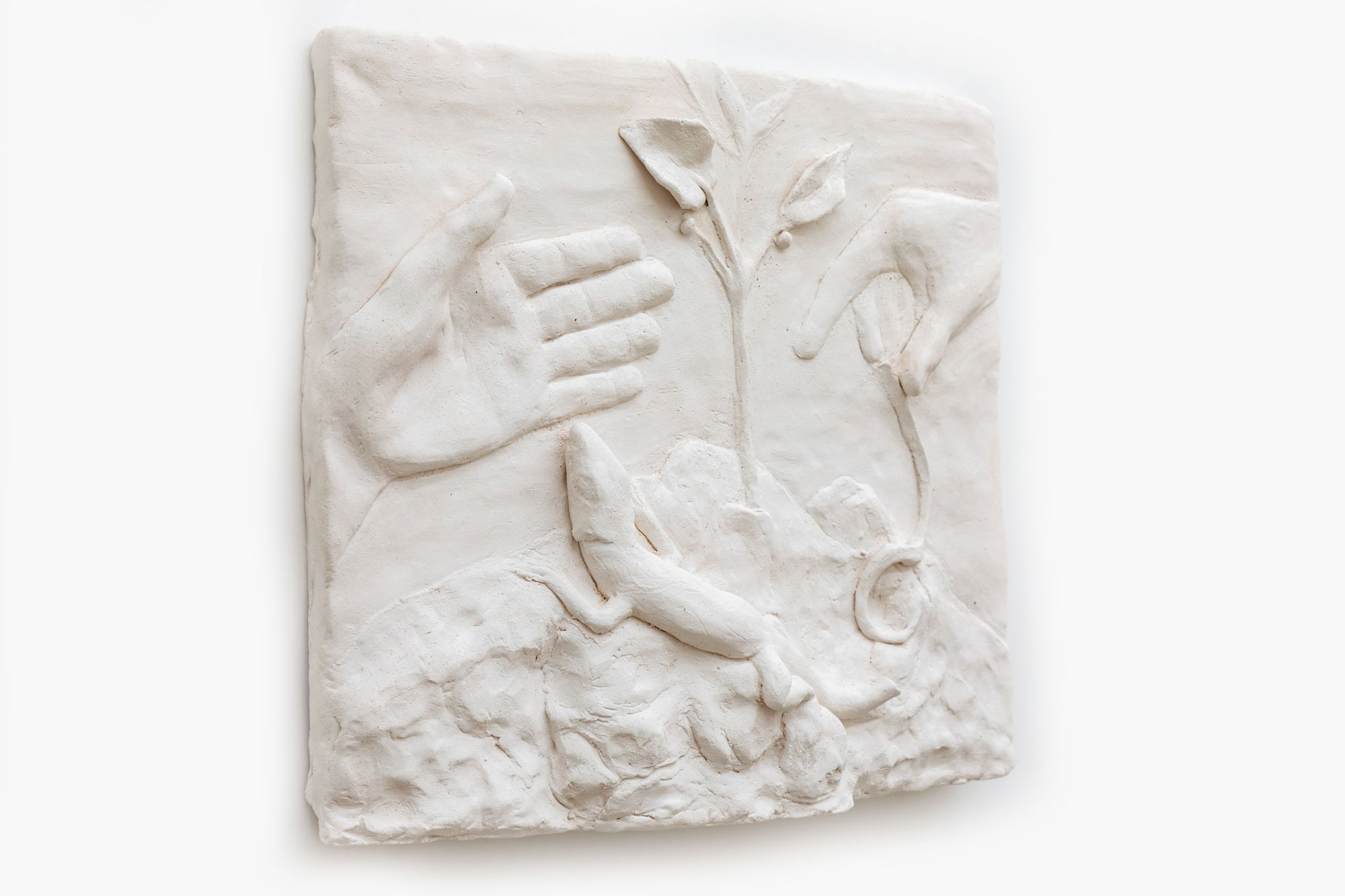

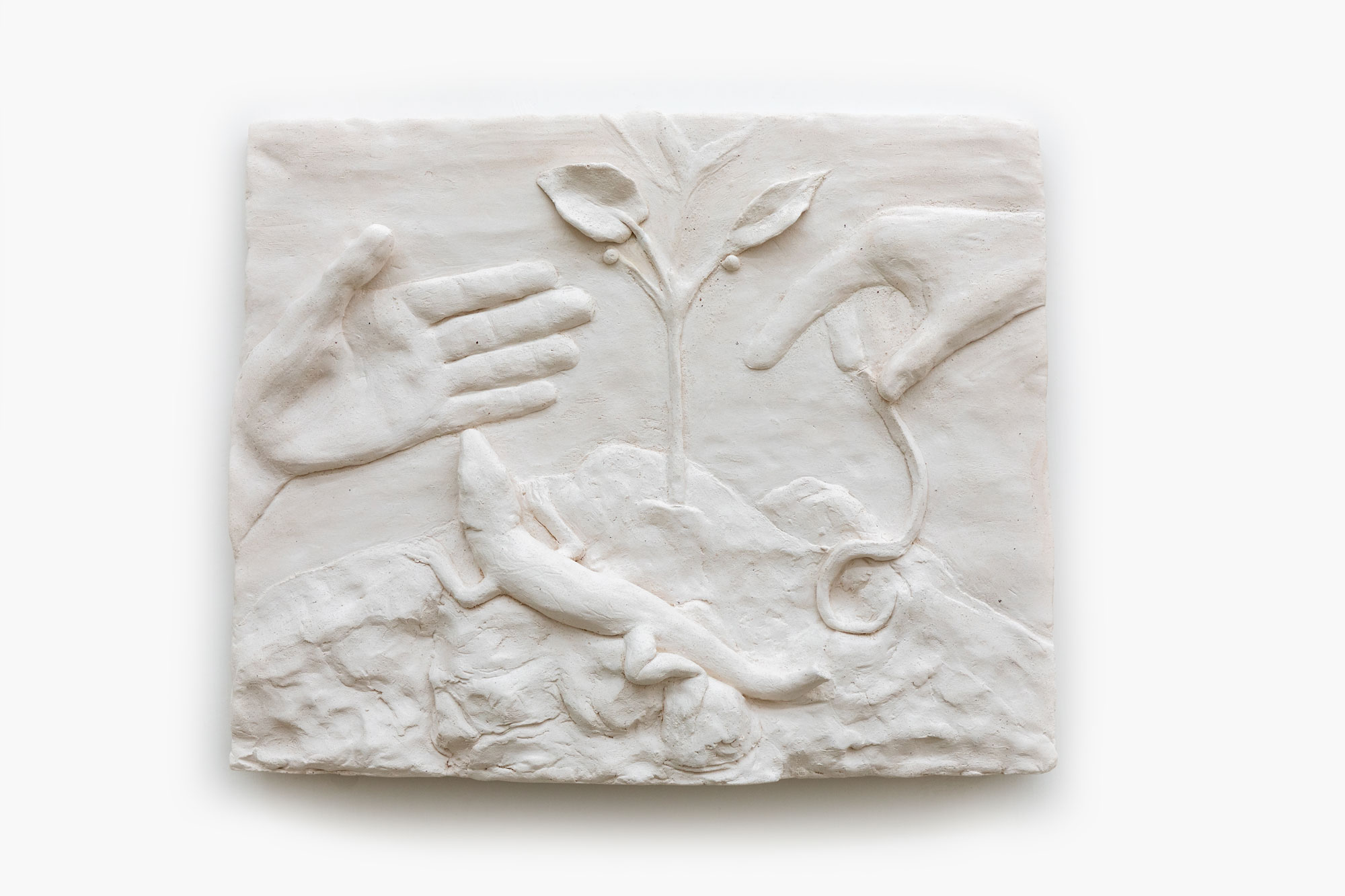

Arranged in continuity with the paintings, the high-reliefs are true miniature theaters, three-dimensional

snapshots that, thanks to their semi-enclosed structure, presuppose an external observer, in addition to the audience, often present in the paintings as well, making the relationship between seeing and imagining more complex—something that theater, and later cinema, brought to its peak tension and expression.

In these works, action is reduced to a gesture, a whisper, or a glance, to a moment of rest. The small

dimensions confer intimacy but do not detract from the power of the two warrior-friends who stand firm and

proud on a ship at sea (Friends on an Adventure) or the girl embracing her fear (Skeleton with Girlfriend).

The subjects of the high-reliefs resemble protagonists of epic mythologies but are not heroes; they are dreamers in fairy- tale settings who seem to have dressed up to stage a new game. It is the game of imagination in this play, Teatrino, where the great puppeteer is the artist himself.

Elena Lydia Scipioni

SOLO

The Artist Room, London (EN)

Curated by: —

Painting

31.05.24—30.06.24

Tired City

It’s difficult to imagine ever getting used to living in a city like Florence. A city where one can walk to Piazza del Duomo and see Giotto’s Bell Tower rising from the ground, or walk alongside the river Arno as the warm sun shines on the Ponte Vecchio. A city where the museums house paintings by Botticelli, Caravaggio, and Raphael as well as sculptures by Bernini and Michelangelo. A city where almost every corner is a feast for one’s eyes.. Per Leonardo Devito, questa è stata la sua realtà quotidiana mentre cresceva circondato dall’imponente storia dell’arte fiorentina.

«Mentre studiavo all’Accademia di Belle Arti a Firenze non ho guardato pitture contemporanee ma solo le cose che c’erano a Firenze», afferma Devito. «Artisti del primo quattrocento toscano, come Fra Angelico o Piero della Francesca, mi hanno formato dal punto di vista dell’immaginario che è sempre presente nella mia attività».

In Rogo, uno dei dipinti esposti nella sua seconda mostra presso The Artist Room a Londra, un uomo è sdraiato a terra e dorme, ignorando la città in fiamme alle sue spalle. Devito dipinge la prospettiva della città con angoli violenti e forti ombre, ricordando la prospettiva convergente utilizzata da artisti rinascimentali, come ad esempio Giotto.

«Non lo faccio apposta», afferma l’artista. «A volte creo dei dipinti e a posteriori mi rendo conto qual’è la matrice di immagini da cui proviene quel tipo di soggetto, forse proviene anche da una memoria nascosta che fa parte del mio imprinting». L’uomo in Rogo è avvolto in un lenzuolo blu mentre i suoi occhi sono coperti da una stoffa più scura e soffice. Devito, quando guardò il dipinto dopo averlo finito, lo accostò alla Ebbrezza di Noè (circa 1515) di Giovanni Bellini. Invece a me le pieghe dettagliate della stoffa blu ricordano le lenzuola scolpite in marmo che avvolgono la statua di Santa Cecilia (1600) di Stefano Maderno a Roma o il velo di marmo che copre il Cristo velato (1753) di Giuseppe Sanmartino a Napoli. «Mi viene naturale riavvicinarmi a quel tipo di immagine», riflette Devito.

«Mi interessa molto il rinascimento ma mi piace anche come il novecento l’ha reinterpretato, ad esempio con Felice Casorati, Giorgio De Chirico e Mario Sironi, per citarne alcuni», afferma Devito. «Sono anche pregno di quel tipo di immaginario e plasticità».

I dipinti che Devito presenta nella mostra «Tired City (Città stanca)» non solo ricordano il romantico rinascimento fiorentino o si riferiscono agli artisti italiani di un passato più recente, ma scorrono direttamente nel nostro presente attraverso l’impronta delle esperienze proprie dell’artista.

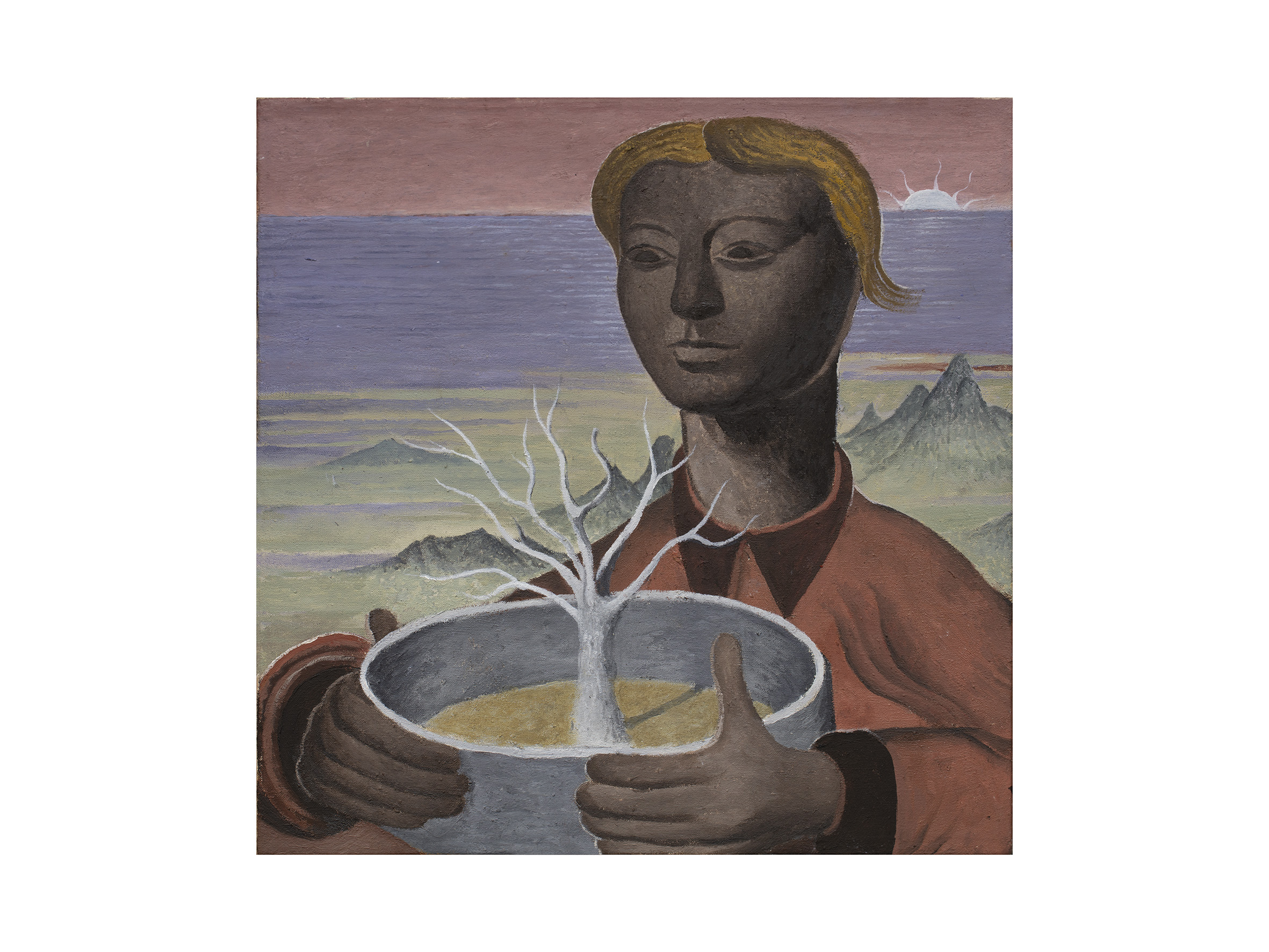

La mostra inizia con Demiurgo, un dipinto nel quale un bambino tiene nelle sue mani una scatola rotonda che racchiude un’albero senza foglie. «Da piccolo, durante la ricreazione, giocavo con i miei amici a fare delle casette per degli gnomi», ricorda Devito. «Prendevamo dei bastoncini, li mettevamo per terra e facevamo dei buchi, e tutti giocavamo insieme a “dare vita” agli gnomi». Con l’albero vicino al cuore, il bambino in Demiurgo è immerso nel piccolo mondo che avvolge fra le sue mani, indifferente a quello che si trova alle sue spalle: un orizzonte infinito con le montagne, l’oceano, e il sole che sorge. Quando chiedo a Devito se gli gnomi fossero giocattoli reali, lui ride e mi dice: «No, facevamo finta che esistessero. Era un momento di fantasia condivisa, in cui si creava una sorta di città inventata». Il titolo del dipinto proviene dalla figura filosofica del demiurgo, un essere divino e artigiano dell’universo, introdotto per la prima volta da Platone nel Timeo. Il bambino del dipinto è il demiurgo del piccolo mondo che tiene fra le braccia, come lo era Devito da bambino delle città inventate che creava con i suoi amici durante la ricreazione e come lo è oggi del mondo che materializza con i suoi dipinti nella sua «Città stanca». Dipinto per dipinto, l’artista ci trasporta in un mondo semi-inventato, un immaginario materializzato attraverso gli occhi di un bambino che cresce.

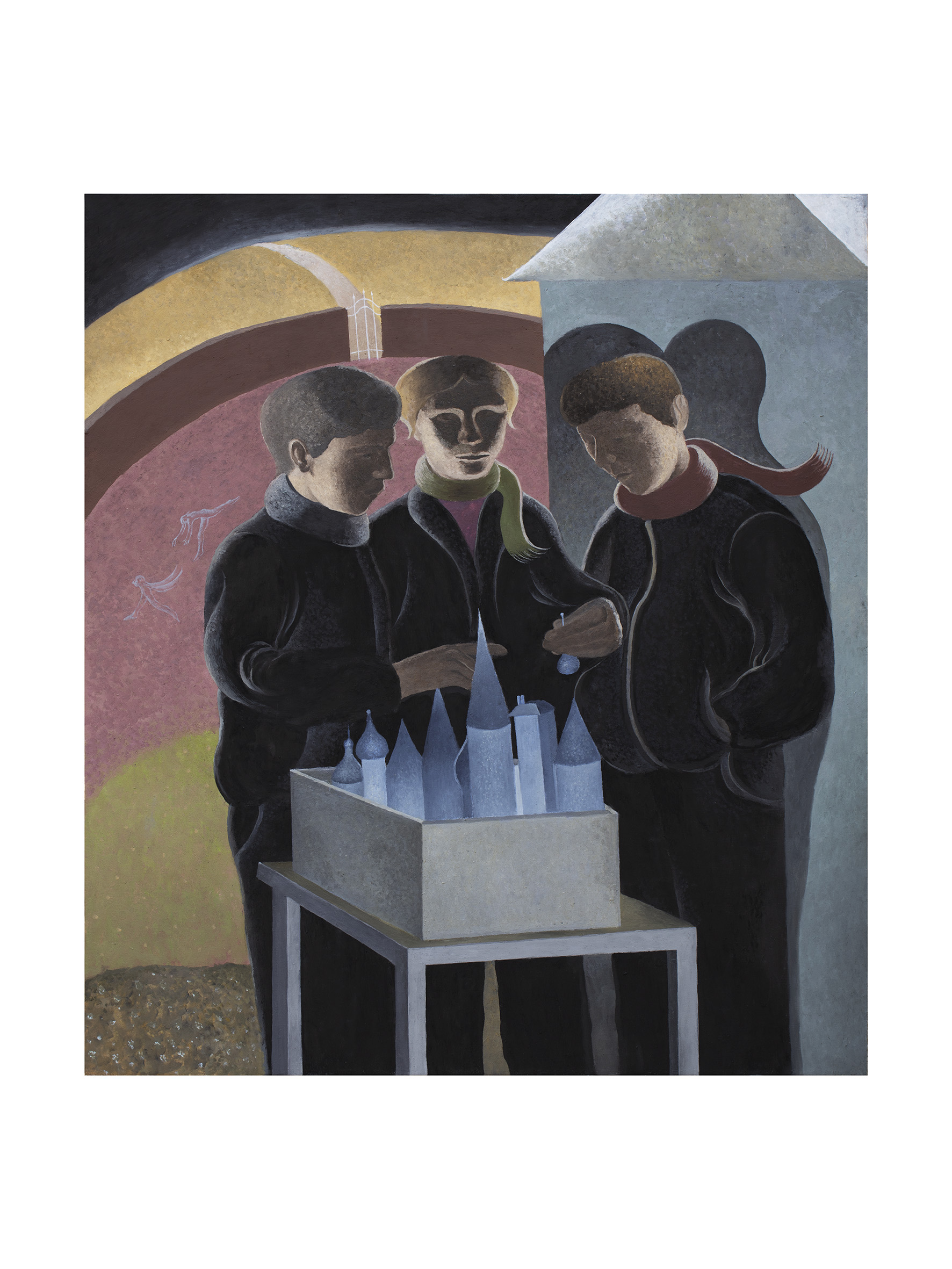

In Primo giardino, più alberi sembrano essere cresciuti nella città rinchiusa e non sono più senza foglie. Eppure, sono tutti traslucidi e sono protetti da tre pupazzetti piccoli e altrettanto traslucidi. «Ho aggiunto quei pupazzetti perché volevo che il dipinto fosse meno serio e più divertente», mi spiega Devito. «Sono come i piccoli giocattoli che trovi negli ovetti Kinder».

La presenza dei “tre pupazzetti Kinder” è quasi impercettibile, quasi nascosti dalle imponenti mura grigio-cemento che racchiudono il mondo degli alberi. I riferimenti a dettagli dell’infanzia non finiscono con i “giocattoli Kinder”.

In Tardo pomeriggio, due adolescenti sono seduti su una panchina, dove uno ha in mano un mazzo di carte mentre l’altro ha una felpa addosso con un disegno quasi sbiadito di un bambino che fa la pipì. Guardando attentamente, la spirale marrone sul retro delle carte ricorda il Gioco di carte di Yu-Gi-Oh! mentre il disegno del bambino che fa la pipì ricorda le decalcomanie popolarmente attaccate sul retro delle macchine o sulle T-shirt di brand come Rams 23 agli inizi degli anni 2000. Con questi piccoli dettagli divertenti, Devito accenna alla specifica ma condivisa esperienza di crescere negli anni 2000. Eppure, li pone in netto contrasto con la fabbrica e il fiume grigiastro che striscia drammaticamente dietro alle spalle dei ragazzi. «Fiume e fabbrica è un po’ il panorama che ho vicino a casa mia in periferia a Firenze», spiega Devito. Lo scontro fra il fumo della fabbrica e i divertenti riferimenti adolescenziali esalta le espressioni indifferenti dei ragazzi mentre fissano come nel vuoto ciò che si trova davanti a loro, oltre i confini del dipinto.

Le espressioni dei protagonisti nei dipinti di Devito si scontrano con ciò che li circonda, avvolgendoli in una sensazione sconcertante. «Non mi piace quando un’immagine è ovviamente felice o ovviamente triste», dice. «Ci deve essere uno scontro fra le due, e quando questo accade, viene creata una certa ambiguità che lascia spazio a qualcosa che deve ancora essere svelato».

In Ricreazione, una oscurità travolge i bambini mentre giocano con la loro città inventata in un momento del giorno scolastico che normalmente sarebbe di divertimento e di piacere. La città immaginaria di Devito diventa un universo alternativo dove mondi sembrano scontrarsi in tutti i sensi, attraverso le emozioni, le esperienze e il tempo.

«È interessante quando, da un punto di vista narrativo, cose del passato si trovano in posti che non hanno nulla a che vedere con loro, come nel film Caravaggio (1987) di Derek Jarman», spiega Devito. Nel film, Jarman crea un ritratto fittizio di Caravaggio includendo scene dove il pittore fuma sigarette o si trova circondato da altri elementi contemporanei che non esistevano durante la sua vita. Eppure, questi elementi sono quasi impercettibili e non sembrano fuori luogo. «Mi piace questo tipo di frammentazioni di periodi», dice Devito.

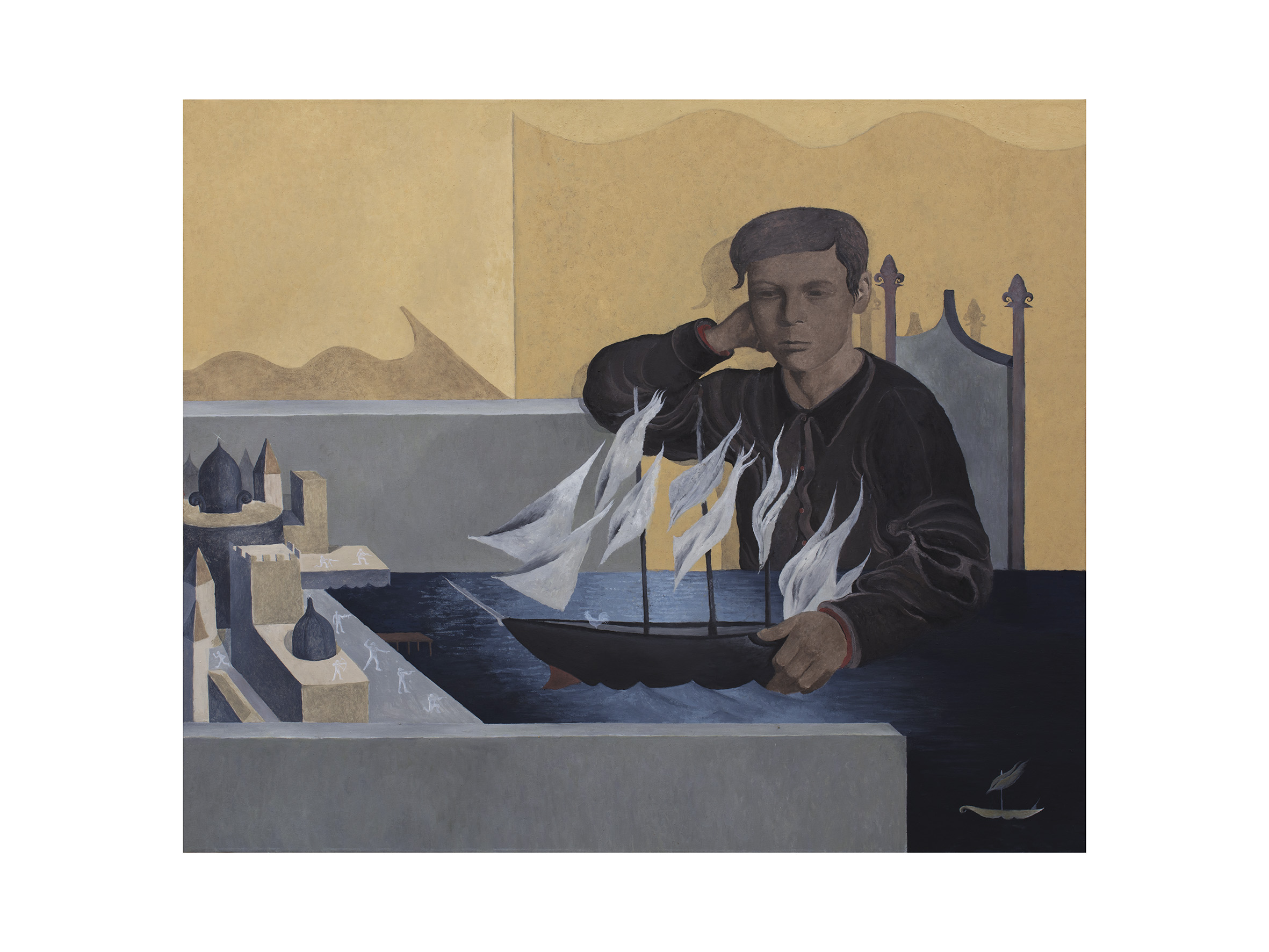

In Assedio, l’artista dipinge piccoli soldati che sparano con fucili a una nave per proteggere un castello medievale. In teoria, i soldati dovrebbero convivere con il loro ambito medievale, e, tuttavia, si ritrovano nel mondo surreale che crea Devito dove passati molto distanti dialogano facilmente con il presente.

Quando uno cresce da bambino in Italia, spesso questi mondi immaginari si scontrano nella vita reale. «Esiste uno scontro costante tra il presente e il passato nelle città italiane, e la immutabilità delle cose», dice Devito. «Ad esempio Genova, è una città bellissima ma ha quei cavalcavia sgradevoli, o Roma, con i cantieri vicino al Colosseo. È tutto un caos ma poi ti rendi conto che di fronte a te ci sono queste rovine bellissime». La «Città stanca» di Devito si collega alla città italiana, dove elementi sconcertanti della vita reale si scontrano e vengono immaginati nel mondo inventato di un giovane ragazzo. «Collegare questi due mondi e dimensioni opposti, il contrasto fra la modernità e l’antichità, è parte di un immaginario che mi affascina».

Il titolo della mostra prende ispirazione dalle Città invisibili di Italo Calvino. Devito mette insieme il reale con il fantastico, proponendo mondi alternativi dove crescere non deve per forza significare vivere in un mondo più cinico. Proprio come Calvino, che usa la vera figura storica di Marco Polo per immaginare le città nell’impero di Kublai Khan, Devito usa la storia impressa dell’Italia e la sua concezione nei nostri ricordi e li intreccia con le sue esperienze personali per creare la sua «Città stanca».

Dal 2020, Devito vive a Torino circondato dal mondo dell’arte contemporanea del capoluogo piemontese, dove la sua «Città stanca» diventa una maniera per guardare indietro, agli incontri fra i ricordi collettivi, le fantasie immaginarie e le esperienze personali vissute.

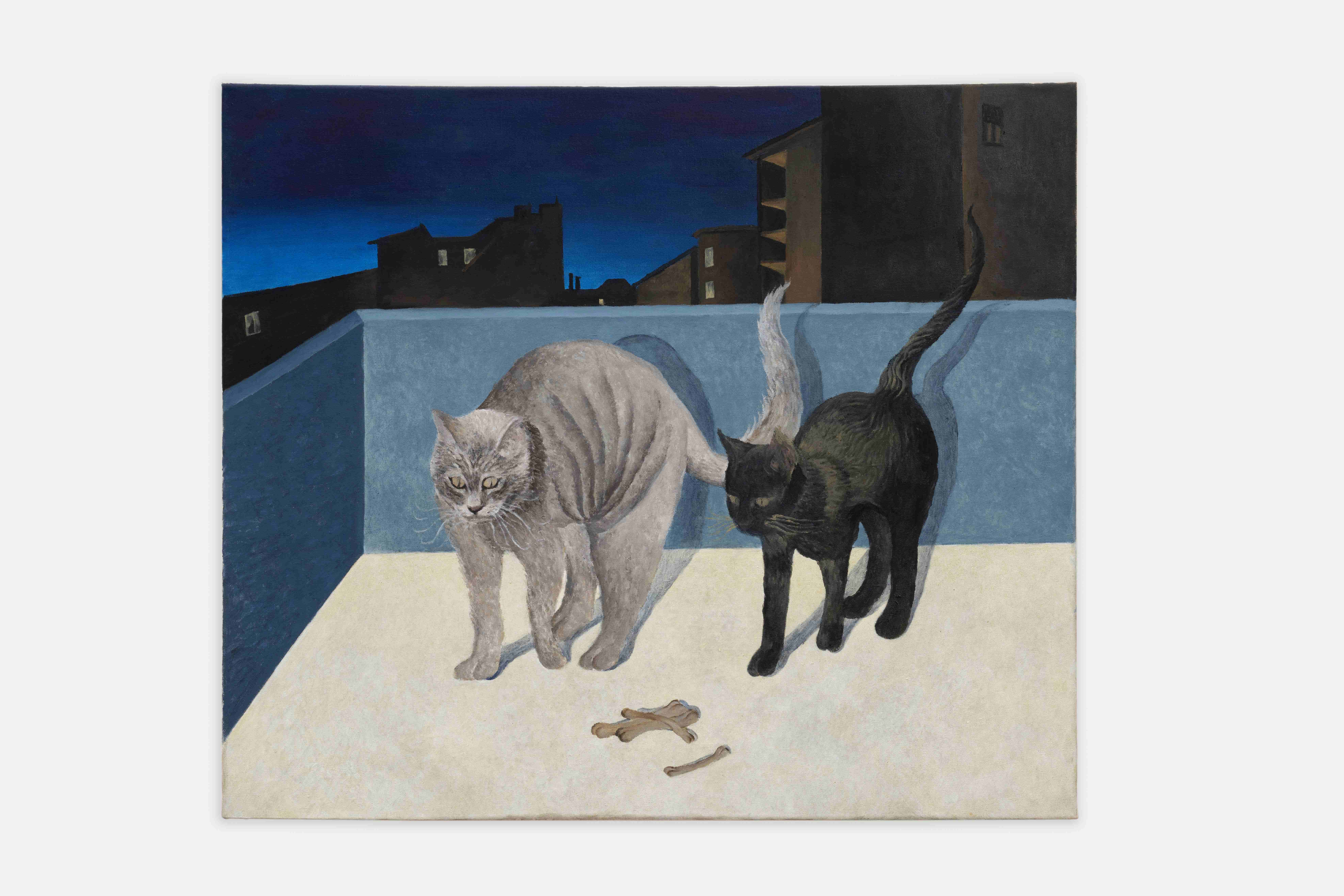

«Il mondo dell’infanzia è tutto bello e ricco. È tutto inventato e felice quando sei bambino», dice Devito. «Poi però cresci e tutto si brucia e sparisce». Il viaggio attraverso la «Città stanca» finisce con Bobi fa pipì, dove due uomini anziani guardano oltre le mura per vedere le ultime rovine della loro città inventata. L’unica cosa che rimane è un albero quasi morto, con un cane randagio nero che fa la pipì accanto ad esso. «Sicuramente rimangono alcuni strascichi di quell’infanzia da qualche parte», riflette Devito.

L’indifferente e annoiata espressione che dominava gli uomini durante la loro infanzia e adolescenza mentre costruivano la loro città sembra essere sparita, sostituita invece da un’espressione drammatica e sconvolta. Tutto ciò che è bastato per farli cambiare è stato invecchiare e vedere un cane sporcare gli ultimi strascichi della loro cara città inventata.

GROUP

The Artist Room, London (EN)

Curated by: Leonardo Devito

Painting

18.01.24—17.02.24

Haunted Garden

The aim of the exhibition is to propose a wide-ranging look at young Italian painters trained mainly between Venice and Florence. I think it is inevitable, living in cities like these, not to remain sterile in front of the historical and artistic heritage, and I am not just talking about museums, churches or monuments, but more about the mysterious nostalgia that these cities know how to conceal, stories that have never been lived and never seen, real or imaginary visions that hide and sediment within their walls, capable of creating new paths and suggestions linked to a physical and at the same time invisible memory of streets, squares and places. The artists proposed, although with very different pictorial research, make this inclination to memory and nostalgia seep from their work, images that need to reconnect with the memory of both a near present and of remote and imaginary pasts. Often drawing on distant references and suggestions. The very title of the exhibition wants to evoke this: a bewitched garden in which plants of all kinds and species manage to grow among the ghosts of the past. As in the works by Michele Cesaratto in which friends and acquaintances of the artist are portrayed in settings and landscapes linked to the artist's childhood places but also reminiscent of early 15th century Italian painting, or as in the paintings by Luca Ceccherini in which themes and iconographies of 14th century Italian painting are represented with a language that takes the borderline between painting and represented object to the limit. Or in the works of Oxana Tregubova in which a sacred and primordial relationship with nature is suggested with a language that is mindful of the artist's intimacy and personal memories. Or as in the works of Sofia Massalongo in which delicate details of gestures and objects of the artist's friends take on the appearance of simple and indelible distant memories through painting. Or as in the works of Miriam Marafioti in which the city its changes and sedimentations are expressed in a landscape painting that investigates the physical memory of specific places. The result that perhaps all these artists have in common is the creation of images that in the end always remain ambiguous, there is never anything unveiled or explicitly ‘pornographic’, they are real images that try to show the hiding place of something remote, the memory of a gesture, a nostalgia for a particular day or a distant world barely perceived, in which we easily lose sight of the border between the real and the magical.

Leonardo Devito

SOLO

Galleria Acappella, Naples (IT)

Curated by: —

Painting, sculpture

16.04.23—05.06.23

My favourite things

«Few things, protected by solid walls, or scattered across the vast Valais landscape, accompany Rilke, like distant and tenacious habits. They live in the vastness of a metaphorical and real landscape interwoven with a thousand voices which, together, participate in a single, powerful melody». The words Sabrina Mori Carmignani uses to introduce the writer’s reflections, poet and playwright Rainer Maria Rilke around the melody of things, and therefore the emotions, meanings and sensations he attributes to them, allow us to identify the relationship that Leonardo Devito weaves with his favourite things, as the title of the exhibition declares. It is, as for Rilke, an intimate relationship with things, a term that identifies not only objects but also certain situations and atmospheres tuned together in a melody.

«Few things, protected by solid walls, or scattered across the vast Valais landscape, accompany Rilke, like distant and tenacious habits. They live in the vastness of a metaphorical and real landscape interwoven with a thousand voices which, together, participate in a single, powerful melody». The words Sabrina Mori Carmignani uses to introduce the writer’s reflections, poet and playwright Rainer Maria Rilke around the melody of things, and therefore the emotions, meanings and sensations he attributes to them, allow us to identify the relationship that Leonardo Devito weaves with his favourite things, as the title of the exhibition declares. It is, as for Rilke, an intimate relationship with things, a term that identifies not only objects but also certain situations and atmospheres tuned together in a melody.

Starting from an imaginary or a subject, such as the well-known Turin market, Devito prefers to give life to a spontaneous narration, leaving room for his own imagination guided by painting which progressively expands the mental image, transforms it and exhausts it. The artistic process is thus more sincere and spontaneous for the artist whose openly playful action is performed on small and medium-sized canvases and bas-reliefs, necessary to be able to grasp his favourite things in their entirety and simplicity. The disinterested and playful character actually seems to become an expedient of defence: offering one’s things of affection can be tiring since it implies extrapolating them from oneself and letting them be looked at from the outside, understanding them without succumbing to them. Thus, the transformation of their pictorial and sculptural restitution into a moment of play allows the artist to take distance from it, which protects him from possible emotional loss. The game, not surprisingly, also becomes the subject of different works: an example is “Gormiti” which, recovering the Byzantine aesthetic in the spatial rendering, shows inert adolescence in front of a childhood that has just ended, for which he feels nostalgia and at the same time the urgency of detachment.

Devito’s ultimate intent is not to create finished narratives, on the contrary, it is to allow the observer to complete the reading of the work through one’s own position of vision which, articulated and complex, awakens distant memories and sensations.

The artist therefore urges us not to let go of the things with which we establish a profound connection: emblematic, in this sense, is the work “Signori Calabresi”, created starting from the drawing by a couple, found by chance, which allowed Devito to bring out a mental place of affection linked to his grandparents, to his distant Calabrian origins, to the colours, to the atmosphere that one breathes there. His artistic sensibility therefore arises from the urgency to return the harvest of his favourite things carefully protected, first delicately cultivated.

Laura Di Teodoro

SOLO

The Artist Room, London (EN)

Curated by: —

Painting

23.02.23—18.03.23

Piccolo testamento

«Some images have a particular meaning for me; they come from personal experiences or from distant stories that I feel involved with or relate to. When I focus on an image, meanings, analogies, contrasts and complementary elements start to emerge that I decide to discard or keep until everything becomes perfectly clear». — Leonardo Devito

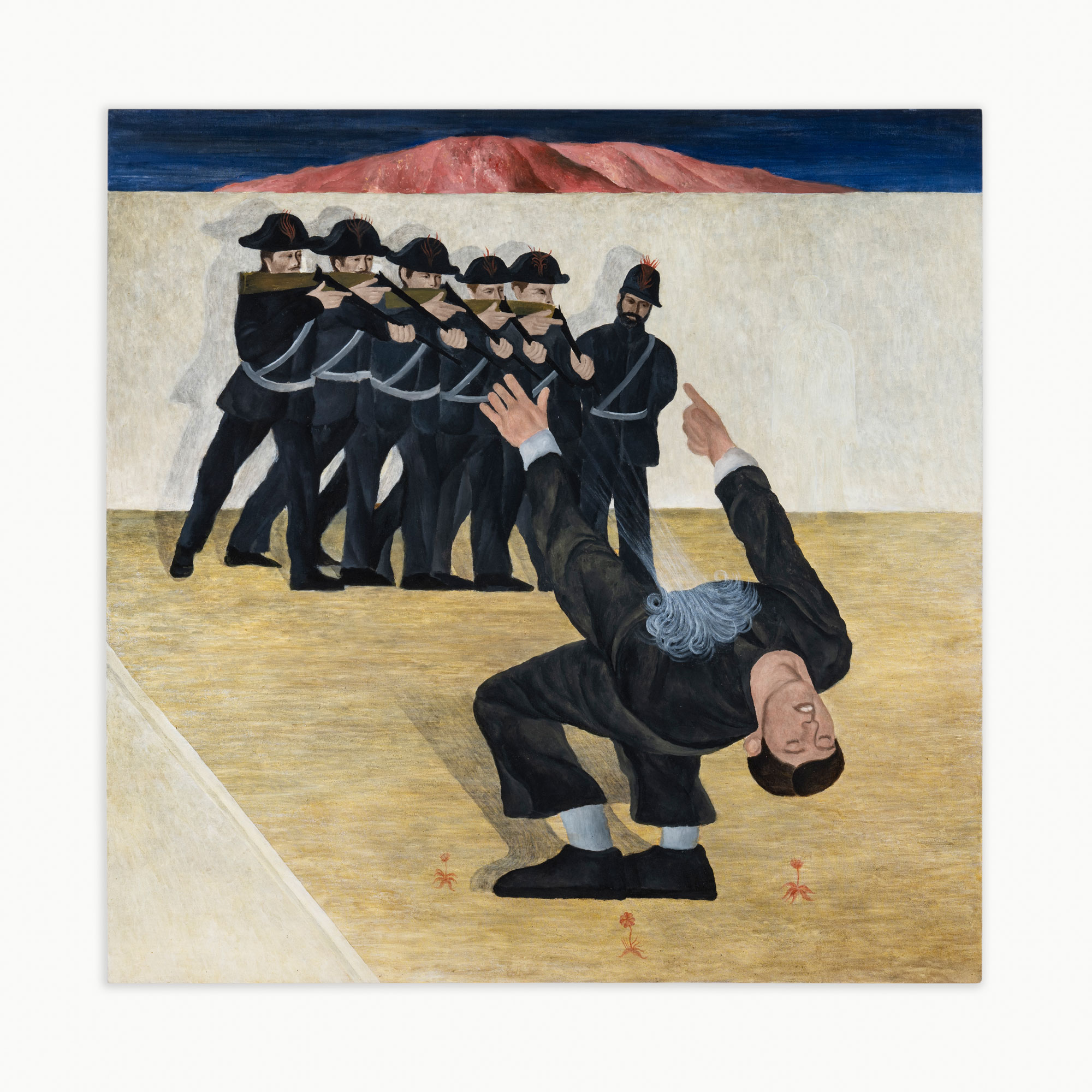

The Artist Room is delighted to present a solo exhibition of new paintings by Leonardo Devito (Florence 1997). This is the artist’s first exhibition in the United Kingdom and his first solo exhibition outside of Italy. Combining autobiographical allegory with interests in religion and literature, Devito’s works are grounded in compelling narratives devised by the artist, often explored through sequences of paintings. The paintings in Piccolo Testamento [Small Testament] relay the story of an adolescent male youth’s hedonistic final days spent on the run in Italy.

Central to Devito’s interest in painting is the potential for images to tell stories. Inspired by medieval Christian and Renaissance cultures, where the creation of religious imagery was necessary to communicate the sacred scriptures to an often illiterate audience, Devito seeks to revitalise painting’s peculiar capacity to carry allegorical and moralistic traits. The artist often borrows compositional elements from pre-contemporary artists, reflecting on how historical events or fables can be understood in present-day terms.

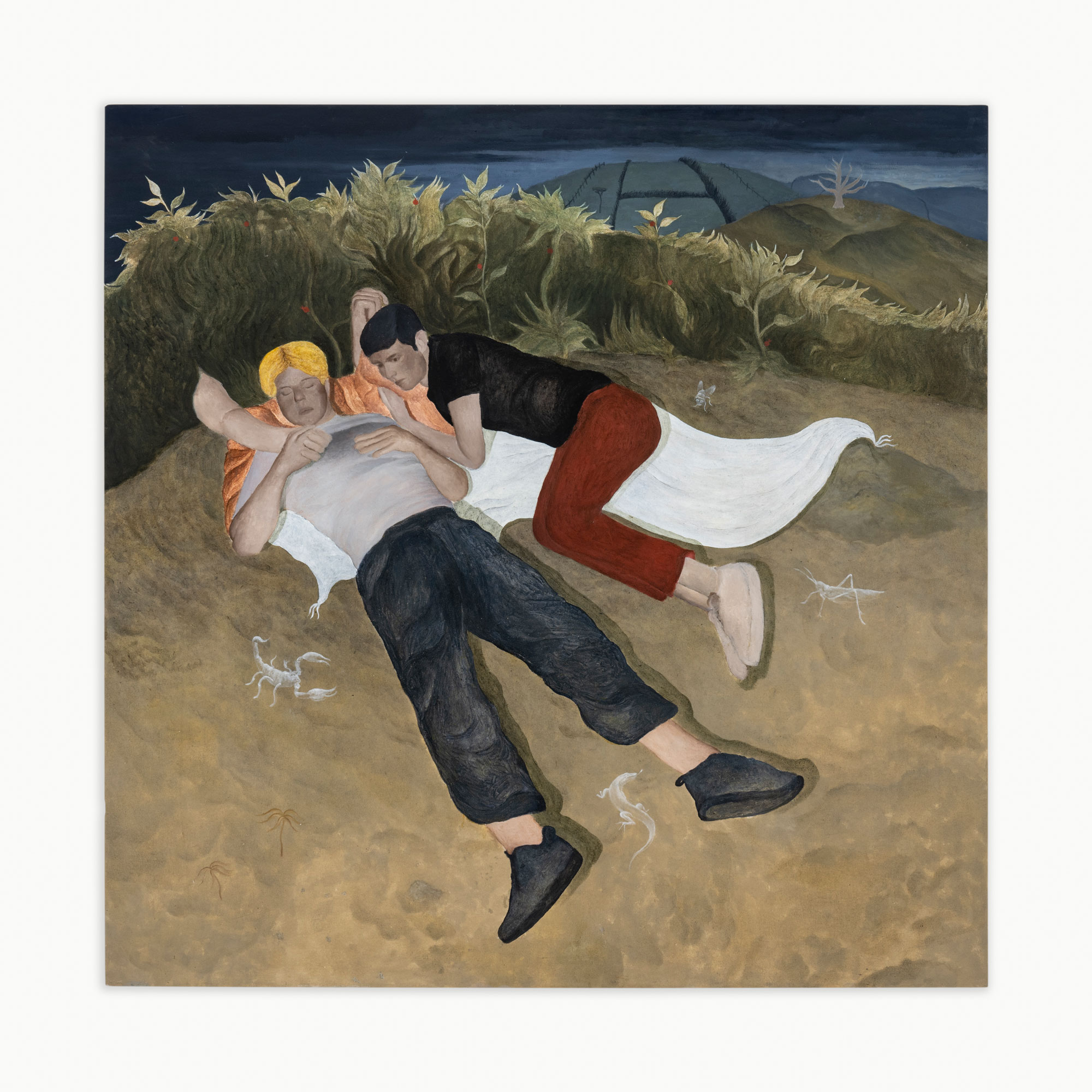

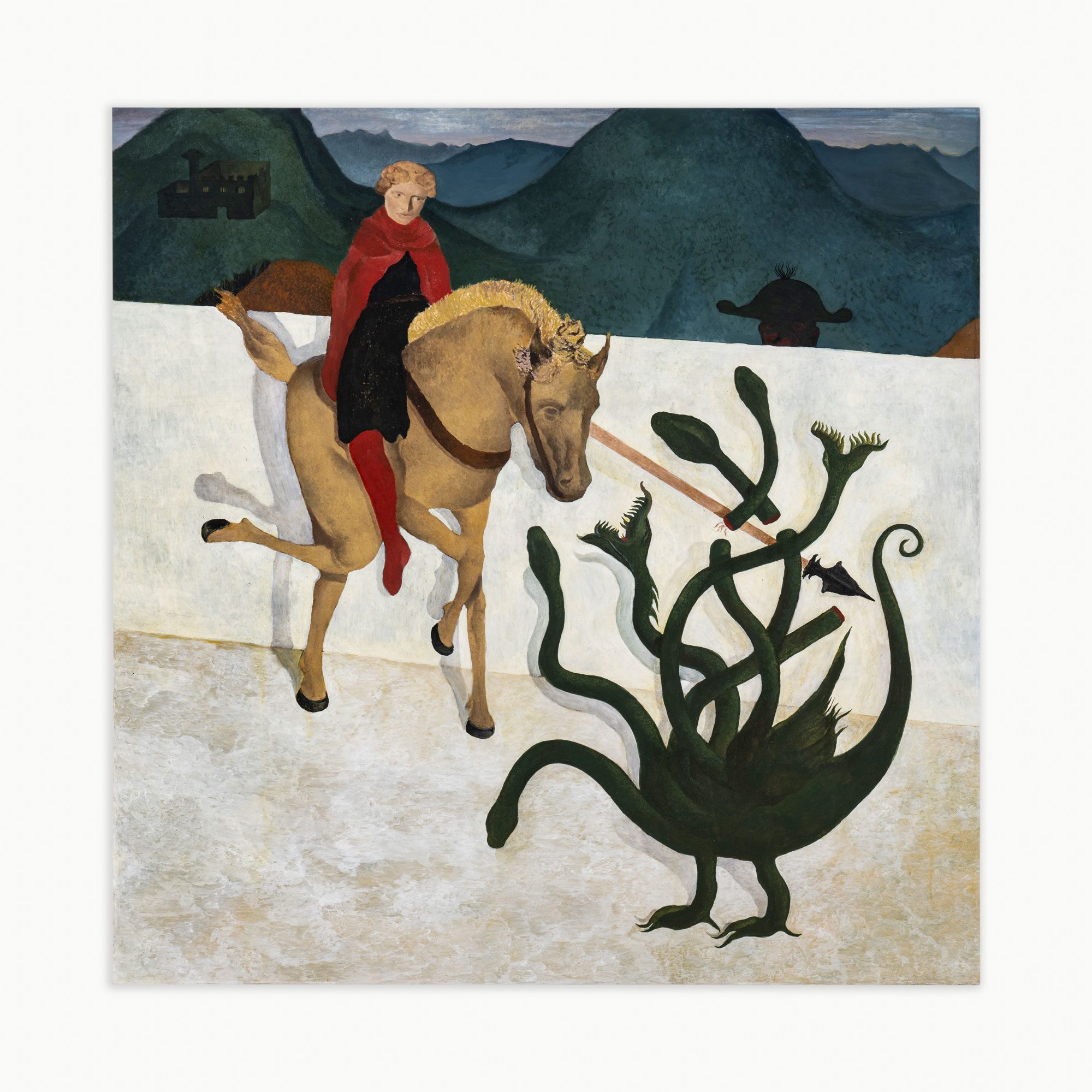

Piccolo Testamento begins with “First time”, a painting that depicts a young couple’s first experience of erotic intimacy together. In presumed elation and bliss, the male figure’s head levitates away from his own body. Later, in “Pickpockets”, the same figure, in a seemingly calmer aura, is witnessed with a friend pickpocketing a figure absent from the frame in a seaside city at night. In “Caccia” three hounds hunt for the boys in the countryside, and the two police officers controlling them fade into the distant woods behind. Meanwhile, in “Sleeping Thieves” the figures rest alongside a bush surrounded by ghostly insects and lizards.

The tree central to the painting “Caccia” is visible in the distance behind, indicating the police are close and arrest appears imminent. Before being caught, the boy has a dream. “Sogno di un prigioniero” depicts a knight appearing to save him; defeating a multi-headed hydra guarding his eventual prison’s walls that can be seen in the distance. The structure of the painting references “Ercole e l’Idra” a tempera-on-panel painting by Antonio del Pollaiuolo that is housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence and Saint George and The Dragon (1502) by Vittore Carpaccio housed in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni of Venice. “Esecuzione”, the final painting in the exhibition, takes place on the opposite side of the wall as “Sogno di un prigioniero”. In this work, the protagonist is being executed by a police firing squad, marking the end of his being on the run. In its structure, the work inverts Édouard Manet’s painting “L’esecuzione dell’imperatore Massimiliano” by swapping the position of the protagonist and those chasing him. Marking the end of his life are three small flowers growing, their vivid colour echoing the vast red mountain on the horizon.

While the works on view can be understood as a whole narrative, Devito asserts how each work can be interpreted on its own terms. «Each painting is an inconclusive story that can leave the viewer with the freedom to conceive a particular narrative» he explains. «The way in which the writing in books leaves us the faculty to be picture totally different images depending on who we are». As such, in his practice, the artist seeks to link two cultural forms (writing and painting) by distilling images that hold peculiarities to define a certain context and an «atmosphere and narrative not unlike that of literature».

Approaching his work, Devito draws from varied sources of interest: fresco cycles of the Italian fifteenth century; the dreamlike atmosphere of Franz Kafka’s novels such as “Il processo” and “Il castello”; stories by Italian writers Italo Calvino and Dino Buzzati; and the practice of reclusive American artist Henry Darger. As such, Devito’s complex worlds, incorporating idiosyncratic and recognisable characters (often situated in dark and dramatic environments) are laden with symbols and parables relevant from historic times to the contemporary. Functioning like a coming-of-age story, the works in Piccolo Testamento tell a familiar saga, of confidence causing conflict and the downward spiral of losing oneself to one’s ego.

Laurie Barron

PRESS

SOLO

Osservatorio Futura, Turin (IT)

Curated by: Federico Palumbo

Sculpture

19.01.23—20.02.23

Ghost dance

The idea for the exhibition arose from the proposal and the discussion which followed with Osservatorio Futura, an independent space located in the San Donato district of Turin. Starting with the assumption that the space has no commercial purposes, the idea of creating a site-specific work was born, with the possibility to use mediums and techniques I do not usually adopt in painting. The proposed name of the work is Ghost dance, and it is composed of eight sculptures designed specifically for the exhibition space, born with the purpose of creating a unique image. The work represents a group of ghostly figures in a dance or action of some kind around a boy who is lying on the ground. The meaning of the image is unclear and open to interpretation. It could possibly represent a group of ghosts in ritual prayer over a dead boy, as well as depict a series of presences disturbing a boy in his sleep. I preferred to leave the ultimate meaning of the work undefined. As the exhibition space consists of a single room, I was interested in suggesting an image with a scenic and enveloping feeln fact, I ideally used as a reference some 15th-century sculptural groups of the Emilian school, first and foremost Niccolò dell’Arca’s “Lamentation over the Dead Christ” in the church of Santa Maria della Vita in Bologna.

When I create an image I am always interested in reasoning in retrospect as to why I chose a particular subject and why I found it particularly evocative. In general, the theme of death interests me a great deal, especially in its relationship to the visual arts and to images in general. The theme of death is intrinsic to the language of photography: any image is the presence of an absence, and this finds its greatest expression in images of deceased persons, which are representations of figures permanently absent in the space and time in which they are made. As early as ancient Egypt, the deceased ideally exchanged their physical, earthly body for the imperishable body of the portrait or funerary mask, a process constantly perpetuated by the relationship between the visual arts and funeral rites. Thus, the image becomes both representation and ghost of the represented object, and in this sense, the boy’s sculpture simultaneously signals his presence and absence, welcomed with a dance from the world of Elsewhere.

Leonardo Devito